|

||

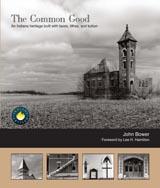

The Common Good, An Indiana heritage built with taxes, tithes, & tuition PHOTOGRAPHY by John Bower, FOREWORD by Lee H. Hamilton |

||

|

||||

Motivation and inspiration for creating The Common Good In the course of creating my six earlier photography books, my wife, Lynn, and I have visited every town and city on the official Indiana highway map. On our many day trips, we often spotted over-grown, one-room schoolhouses and closed-up, small-town high schools. We also discovered abandoned churches, left-behind courthouses, forlorn community hospitals, and deteriorating county homes. While I had photographed a few of these relics over the years, I hadn’t systematically sought them out. Then, one day, Lynn suggested it might be time to do just that. I agreed, and we began a magical year looking for these nearly forgotten buildings and objects that were constructed for the betterment of us all. It didn’t take long before we began finding totally unexpected treasures, such as a derelict mental hospital; former Defense Department plants; some wonderful, but disintegrating, community treasures of Gary; and many others. All these places were proudly constructed for the needs of fellow citizens. But, when they had out lived their usefulness, many were simply left to the ravages of the elements. It’s my hope that The Common Good will remind all Hoosiers of how essential these places once were, and how they still deserve our continuing respect. The Common Good is OUT-OF-PRINT and no longer available. |

||

The Journey... Over the years, Lynn and I had driven by many old, retired schools and churches. In fact, there were a few in our first book, Lingering Spirit. But, now, they were beckoning us to photograph them much more comprehensively—throughout the state. Lynn came up with the book’s subtitle first—An Indiana heritage built with taxes, tithes, and tuition—then added the title, The Common Good. Before starting, we decided it made sense to include various public buildings as well. Closed-up schools were the most numerous. We found them made of brick or frame construction, one-room or two, as well as multi-story pre-consolidation high schools with fancy, carved stone entrances. And gymnasiums—one with no floor whatsoever, another whose leaky roof led to vegetation growing in the soggy maple planks. Inside one school, we found a dead piano, lying on its back; in another, a trap door leading down into what could have been a great a place for unruly pupils. A few buildings still had their bell towers (mostly without the bells). In some cases, the splotches of light falling through holey roofs made interesting patterns on the interiors. There were arch-topped, pointy topped, square-topped, and round-topped windows and doors, most with broken or missing glass. Sometimes metal or milk-glass doorknobs offered entrance; other doors were locked with latches, padlocks, or chains. It wasn’t unusual to find a gaping hole in one end so farm equipment could be stored inside. We found old school desks with holes for ink pots, original wainscoting, remains of slate blackboards, holes in ceilings where pot-bellied stoves discharged spent gasses, worn pine floors, encroaching vines, names carved in limestone, an old cast-iron water pump, and school buses (one sans engine and wheels). We visited Dead-Man’s College in Fulton Co., James Dean’s high school in Fairmount, and Indianapolis Arsenal Technical High School where we were treated to a tour of the tower with its giant gears and pulleys that had been used to unload military equipment in the 19th century. There were also plenty of small, medium, and large churches built of various materials and in a variety of designs. I particularly liked one from 1854 and another from 1860 because each had remnants of original shutters. We found different denominations: Methodist, United Brethren of Christ, Christian, Quaker, and a beautiful synagogue in downtown South Bend. There were three empty St. Mary’s Catholic Churches—a large one in Washington, a medium-sized one in Diamond, a small one in Derby. The former St. Joseph’s Catholic Church in Indianapolis had been holding services for 100 years when the congregation moved away in 1979. In Posey and Crawford Counties we found “kirches,” with their names spelled in German. Most impressive was the magnificent, limestone First Methodist Church in downtown Gary, which cost $625,000 to build in 1925, but now looked like a WWII European ruin. A much smaller Zion Chapel, in Switzerland Co., made of rough stone, had a collapsed ceiling. In Indianapolis, the Central Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church was badly deteriorating when we visited, and the Methodist Episcopal Church in Bobo had its steeple carefully cut off and placed upright on the ground nearby. The saddest sight was a stained glass window in Jay Co. that was peeling out of its frame like a the skin of a banana. The public and municipal buildings we found were equally varied. We visited former courthouses in Shoals and Cannelton that now housed, not government servants, but local historical societies. The beautiful old Indianapolis City Hall sat empty, as did state hospital buildings in Evansville, New Castle, and Indianapolis. I photographed a water treatment plant, jails, a police station, a fire station, county homes, fire engines, and a 1953 Chevy police car that had been rear-ended in a parade. In Gary, I shot a small closed-up hospital, which had been for blacks in the city’s segregated past, and the 1936 main post office. We enjoyed exploring the retired buildings at the Kingsbury Munitions Factory in LaPorte County, Jeffersonville’s Quartermaster Quadrangle (later restored), and the National Military Home in Marion. I shot three former electric light plants, a small hydroelectric operation in Baintertown (which still had its 1925 generator), and “Old Sparky,” Indiana’s electric chair—which had delivered the ultimate punishment 62 times. We couldn’t have been more pleased when Lee Hamilton agreed to write the Foreword. After serving southern Indiana for 34 years in Congress, he had remained active in working for the common good as Director of the Woodrow Wilson International center for Scholars and as Director of the Center on Congress. He also regularly served on important committees such as the 9/11 Commission—and he did an outstanding job writing a timely and relevant Foreword. |

||