|

||

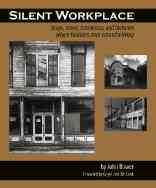

Silent Workplace: Stores, shops, businesses, and factories where Hoosiers once earned a living PHOTOGRAPHY by John Bower, FOREWORD by Gayle and Bill Cook |

||

|

||||

Motivation and inspiration for creating Silent Workplace While driving thousands of miles throughout Indiana, Lynn and I couldn’t help seeing hundreds of empty storefronts, factories, and other various closed-up businesses. Their haunting presence reminded me of my family’s gift store in Lafayette, my grandparents’ café and my Uncle Conrad’s bakery in Fowler, my Uncle Harold’s drive-in in Goshen, as well as the massive National Homes and Magnavox plants where I worked at as a draftsman many years ago. Those businesses had once all thrived, but were now all defunct. Some of the buildings they occupied acquired new tenants, some become perpetually vacant, and others were razed. So many places that buzzed with economic activity—now forever silent. After realizing the extent of businesses from Indiana’s enterprising past that had disappeared and would likely be forgotten, I decided to photograph empty commercial structures in imminent danger of also being lost from our memories, as well as from our landscapes. Small-town general stores to big-city factories—all these had been once been vital to so many Hoosiers. But, what were their names, what did they make, what did they sell, what did they offer to supply? Very few of us know the answers anymore. Yet, they provided opportunities for vast numbers for goods, services, and steady incomes. Because of this, each deserved a final portrait as my own personal homage. Silent Workplace is OUT-OF-PRINT and no longer available. |

||

The Journey... During the year Lynn and I spent working on After the Harvest, looking for grain elevators and feed mills—many of which were defunct—we passed by all sorts of other closed-up businesses, and knew they needed to be highlighted in a book. But we didn’t shoot them when we saw them, because it would have delayed our elevator project. So, Lynn had kept a running list of interesting places to photograph for our next endeavor, which she titled Silent Workplace—Shops, stores, businesses, and factories where Hoosiers once earned a living. By the time we were ready to begin, we had a decent list of businesses to photograph, but we also planned on exploring some of the cities and towns we’d never been to in northern Indiana, as well as ones we’d visited only briefly in the southern half of the state. We certainly found plenty of CLOSED signs, but there were scores of businesses that didn’t need a sign. Some were wide open, so we could enter and wander around easily. Others were locked up, and merited tracking down someone with a key. Like the six-story, brick, former Connersville Furniture Co. When first opened in 1882, its machinery was powered a large paddle wheel, which was turned by water flowing underneath the building, that had been diverted from the nearby Whitewater Canal. When we first spotted the building, we learned it had recently been purchased by the Community Education Coalition and was slated to be restored for use as office space. Inside, each story had a row of sturdy wooden columns down the center, which supported a series of heavy cross beams, on which rested the joists of the floor above. The columns on the first floor were the heaviest, and they got progressively smaller the higher the building climbed. It was a magnificent building. We also found many buildings that had been in operation for over a century, but now sat empty. There was Childcraft Industries in Salem, Corydon’s Keller Manufacturing Co., and the Jasper Cabinet Co., all furniture companies. The Butler Company, best known as a manufacturer of windmills, was in the process of becoming an industrial museum, while South Bend’s Muessel Brewery Co. (sold to Drewry’s in 1936) sat empty with gaping holes in the walls where salvagers had removed the giant brewing tanks. We were given a tour of the recently closed Robertson Corp. (originally Ewing Mill Co.) by Phil Robertson, great-grandson of the founder. The Ft. Harrison Savings Bank in Terre Haute, with a large limestone eagle gracing its façade, was razed not long after I photographed it. I also shot the Indiana Brass Co. in Frankfort, Madison’s Eagle Cotton Mills Co., Midstates Wire in Crawfordsville, the once-magnificent Williams House Hotel in Worthington, a group of red-brick Richmond Gas Company buildings, McCray Refrigeration in Kendallville, and the Shafer Glove Factory in Decatur. In New Albany, the Moser Leather Co., had produced leather for Harley Davidson. All closed after being in operation for over 100 years. The variety of closed businesses was amazing: a small store in Levenworth had mussel shells on the ground with holes punched in them for button blanks, the Marble Hill Nuclear Power Plant was abandoned before being finished, the former Singer Sewing Machine factory in South Bend, several general stores, an ice house, drive-ins, movie theaters, Cora’s Beauty Parlor in Marengo, barber shops, and stores that housed who-knows-what. There was the Indiana Wagon Co. in Lafayette that was later Warren Paper Products, the Medora Brick Plant with its beehive-shaped kilns, another brick factory in West Terre Haute, grocery stores, restaurants, a Root Beer Stand with a Hires keg that was closed in 1962. Just outside Kramer we visited Mudlavia, an old spa and, in Montezuma, we smiled at the Third Strike Tavern, whose name seemed to foresee its closing. I photographed a huge oven at Golden Castings in Columbus, and a Detroit Rotostoker boiler at the Mt. Vernon Milling Co. Anita Werling gave us a tour of the Delphi Opera House, which had been built in the 1860s, then closed in the early 1900s. Not long after I photographed the Dutch Mill Service Station in Disko, it was torn down. Rock wool insulation (a precursor of fiberglass) was invented at Banner Rock Products, whose buildings were abandoned in Alexandria. I also shot three closed limestone mills in Monroe Co., an undertaker’s shop in rural Dubois Co., and a great sign in Shirley—of a 3-dimensional fat man in striped pants and chef’s hat, atop a steel pole, holding a lunch pail advertising Judy’s Carryout. When I first asked Lynn who she thought we could ask to write the Foreword, she immediately suggested Gayle and Bill Cook. They’d founded Indiana’s most successful group of companies, so it would be a bit ironic for them to write about failed businesses. But they also were responsible for restoring historic properties, and were very interested in Indiana’s heritage. While the Cooks lived in Bloomington, we’d never met them, but we knew Gayle volunteered at the Monroe County Historical Museum. So, I contacted the director, and she forwarded an email to Gayle for me. Several days later, after I’d sent her some sample images, and a draft of my Introduction, she invited me to their home and we talked over the project, after which she said she and Bill would be happy to write something. They’d recently rehabbed and reopened a small general store in Laconia, and the opulent West Baden Springs Hotel in Orange Co., so they were the perfect couple to write about the mission Lynn and I were on to preserve—in photographs—Indiana’s defunct businesses. |

||